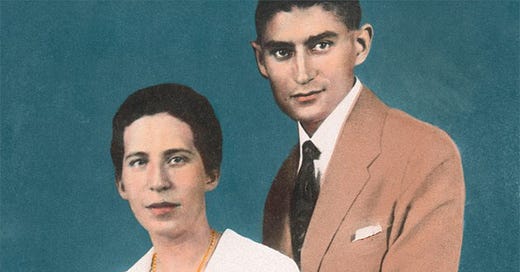

You see, Felice, you have already begun to suffer at my hands; it has started and God knows where it will end. And your grief, I can see it quite clearly, is more specific, more unpleasant, more extensive than any suffering I have so far inflicted upon you. The question of whether I am to blame need not be considered at all, and even the occasion might almost be ignored. What matters is that you have suffered a great injustice, and this alone has to be considered—i.e., my attitude toward it and what the whole thing signifies.

It is entirely immaterial whether my mother is right or wrong. She is right, unquestionably, and more so than you imagine. She knows practically nothing about you, other than what was in the letter you once wrote to her. Apart from this she has merely heard from me that I wish to marry you. That is all she knows, since not a word can be got out of me. I am unable to talk to anyone, least of all my parents. It seems as though the very sight of those I sprang from fills me with dismay. Yesterday by chance all of us—my parents, my sister, and I—were obliged to walk for about an hour in the dark along a muddy road. Needless to say, in spite of all her efforts, my mother walked in so clumsy a fashion that she got her shoes, and undoubtedly her stockings and skirts as well, covered in dirt. Yet she was firmly convinced she might have been in a far worse mess, and on reaching home asked me (in fun, of course) to acknowledge this fact by inspecting her shoes—to testify that they were really not so very dirty. But believe me, I was quite incapable of looking down at them, because I was repelled, and not, as you might think, by the dirt. By then, however, as during the whole of the previous afternoon, I had come to feel some little affection, or rather admiration, for my father for being able to put up with all this— with my mother and me, my sisters with their families in the country, and the confusion in their summer home where cotton wool is to be found lying among the plates and a disgusting assortment of all kinds of objects on the beds; where one of my sisters, the middle one, is lying in bed with some slight throat infection, while her husband sits beside her and in fun as well as in earnest keeps calling her “My Precious” and “My All”; where the little boy, because he can’t help himself while being played with, does his business on the floor in the middle of the room, where the two maids jostle each other in the performance of various duties, where my mother insists on waiting on everyone, where bread is spread with goose-drippings which, if one’s lucky, trickle only down one’s fingers. I do supply information, don’t I? Yet I am really getting it all wrong when I seek an explanation for my inability to put up with all this in the circumstances rather than within myself. Everything is a thousand times less unbearable than I have described here or before, but my repugnance when faced with it all is a thousand times greater than I could ever describe. It is not because they are relatives that I cannot bear to be in the same room with them, but merely because they are people; and I am going out there on Sunday afternoon, though fortunately I am under no obligation, for the sole purpose of proving it once again. Yesterday I was so choked with loathing that I groped for the door almost as if it were dark, and I was far from the house and out on the road before I felt better; but I had stored up so much of it that I still haven’t rid myself of it, even today. I cannot live with people; I absolutely hate all my relatives, not because they are my relatives, not because they are wicked, not because I don’t think well of them (which by no means diminishes my “terrible timidity,” as you suggest), but simply because they are the people with whom I live in close proximity. It is just that I cannot abide communal life; what’s more, I hardly have the energy to regard it as a misfortune. Seen in a detached way, I enjoy all people, but my enjoyment is not so great that, given the necessary physical requirements, I would not be incomparably happier living in a desert, in a forest, on an island, rather than here in my room between my parents’ bedroom and living room.

It certainly was not my intention to make you suffer, yet I have done so; obviously it never will be my intention to make you suffer, yet I shall always do so. (The business about the inquiries is of no importance at the moment; my mother did nothing about it on Friday because she wanted to discuss it with my father; there was no letter from you on Saturday, and with my sense of guilt toward you, I asked my mother to wait, since on Sunday there was again no letter from you; that afternoon I withdrew the permission I had given my mother.) Felice, beware of thinking of life as commonplace, if by commonplace you mean monotonous, simple, petty. Life is merely terrible; I feel it as few others do. Often—and in my inmost self perhaps all the time—I doubt whether I am a human being. The wrong I have done you is only the fortuitous occasion for my realizing it. I really don’t know what to do.

Franz